I have a confession to make. I’m allergic to fanfic.

I have a confession to make. I’m allergic to fanfic.I’m not kidding. I swore off reading fanfic a few years ago when I got physically ill from reading a supremely wrong story. I got nauseous, I broke out in a cold sweat, and I had a fever, stomach cramps and a migraine all night after reading it, until I finally got up at five in the morning and rewrote the ending the way it should have gone. Then, mysteriously, I fell immediately asleep and was fine when I woke up. I haven’t read fanfic since, except for what my students bring into class.

For the uninitiated, “fanfic” is short for “fan fiction”—unauthorized stories written in an established fictional universe, usually one established under someone else’s copyright. Fanfiction can be taken from books, movies, comics, television shows, even plays and popular songs. Sometimes they explore aspects of the story not covered in the canon materials—what did Character A do while the novel followed Character B on his quest for two chapters?—and sometimes they explore avenues of the source material the author deliberately chose not to explore—sure, Characters A and B are in love on the show, but what if it were Characters A and C? This last has given rise to what’s known as “slash” in fanfic—romantic relationships between characters of the same sex, especially male characters who are otherwise portrayed as heterosexual. (The earliest examples were Kirk/Spock stories … and there I’ll leave you.)

I don’t have much of an objection to fanfic personally. Many of my earliest short stories were basically fanfic, although I didn’t know the word when I wrote them, back in elementary school—and, unlike most current fanfic writers, I didn’t put the material online. I wrote it down in a notebook and passed it to a couple of fellow fans, and that was the end of it. It gave me a chance to hone my skills as a writer while I figured out how to establish my own characters and universe. That’s the major reason I support fanfic as a teaching tool, and let my students work on it in class if they’ve got all their other work done: it’s a ready-made story kit that can help you get started in writing. If you’re not yet confident enough in your own authorial voice, it’s sometimes a worthy exercise to use someone else’s to get the hang of things. Writing other people’s characters, mostly to amuse myself, taught me the basics of dialogue and plot and description. And whenever I brought out a new side of an established character, I honed the skills I would eventually bring to my own fully developed imaginary people. But I regarded my own efforts mostly as personal entertainment, and as educational exercises, much like an art student learning to paint by copying the works of the old masters. As long as you don’t hang your copy in a gallery and try to pass it off as the real thing, what’s the harm?

Well, it turns out there’s some very real harm, after all.

Today, of course, there is a large and vital fanfiction community online, and you can find thousands of fics on any subject you can imagine. People read and comment on them, argue about them, respond with writing of their own. Most active fanfic communities have produced more words about their chosen subject than the source of that material has published in the canon—the Sherlock Holmes and Harry Potter communities, for example, have published the word-count equivalent of every Sherlock Holmes and Harry Potter story a hundred times over (at least). Fanfic ranges from the innocuous to the obscene, from the touching to the twisted. And it’s creating a bit of a problem for the people who care about things like copyright infringement.

The basic problem with published fanfic—the stuff that’s out there on the interwebs for everyone to see—is that it’s out there without the permission of the copyright holder. J.K. Rowling has not authorized the million-and-one fics out there speculating on a romantic relationship between Harry and Hermione (or Harry and Draco). And to the extent that people are reading the fics rather than Rowling’s books, the fic writers are stealing Rowling’s business. That may not be much of a problem for J.K. Rowling, considering a) that she’s richer than some small countries and b) that in my experience the Harry Potter fanfic writers obsessively buy and read Rowling’s books to support their writing, but Harry and company are still Rowling’s creations, and she still has the right to decide what does and does not happen to them. That may not matter to the average blog troll, but if you care about a fictional universe enough to write about it, you might want to spare a thought for the author’s feelings.

There are some fairly complex legal arguments on both sides of the fanfiction question. Supporters claim that fanfiction is a “transformative” use of the canon property—a legalese word that means it’s different enough that it’s not infringing. Opponents call it outright theft. Some authors, including Rowling and Stephenie Meyer, have said publicly that they approve of fanfic set in their fictional worlds, and even linked to fics from their own sites. Others, including Anne Rice and Raymond E. Feist, have demanded that fics based on their works be taken down. A large number of copyright holders simply turn a blind eye as long as fanfic writers aren’t actually turning a profit on the work. (This may be because they don’t care, or because there’s only so much satisfaction you can get out of suing a fifteen-year-old English nerd for copyright infringement.) As often as not, it seems to come down to the individual preference of the author or artist who owns the copyright to the original work.

Recently I’ve been asked for my views on fanfic. A couple of Masks fanfic stories already exist—although, since most of them were written by my friends as a gag, they may qualify properly as friendfics. I honestly hadn’t given much thought to the fanfic question until one of my students began bringing anime fics into my class and asking my opinion of them—at which point I discovered that a) fanfic made a terrific teaching tool and b) I was acutely uncomfortable with its publication—the putting-it-on-the-internet part. Discovering the wide range of responses to fanfic didn’t really help me figure out how to guide my students. I finally decided I’d have to set some ground rules for my own fiction—because as far as Masks goes, I’m the copyright holder and it’ s my way or the highway, at least so far.

So, because Masks is an adventure story for teens set in a vivid fictional universe with a lot of side characters with a lot of bunnytrail and alternate-relationship potential (read: a prime candidate for fanfic), I’ve decided to lay down some ground rules here and now, before it becomes an issue. I am speaking only for myself and only for the characters and stories to which I hold copyright. But if anyone asks, ever, about fanfic set in the Masks universe, here are the three rules under which it’s completely fine by me (and only me).

Yeah, I know it’s silly to be laying down fanfic rules for a book that’s not even published yet. But what can I say? It’s been a slow blog week.

1. Don’t charge for Masks fanfic. This is an easy one, and a common restriction for fanfic writers. If you’re writing stories for your own amazement and amusement, you don’t need to charge money for them. Internet publishing is free. If you’re not charging for your work, you’re not poaching on my domain—because let’s face it, the only person who gets to charge for writing stories about my characters right now is me. If you want to be paid for your labor, write something original to you and charge as much as you like for it. (It’s what I did!)

2. Don’t pass Masks fanfic off as canon. This is more of a courtesy issue. I grant that some fanfic may be very, very good—certainly my students’ work is better than the average fics I remember. On the off chance that someone could mistake your work for mine, say somewhere that it’s not mine. I don’t want people getting mixed up on Captain Catastrophe’s secret origin. I wrote it the way I did for a reason. So if you’re going to change it, posting a disclaimer somewhere would be nice.

3. Don’t ask me to read your Masks fanfic. This is nothing personal to you as a writer. It’s partly a legal issue and partly a health issue. I do not read fanfic, except for what my students bring me, mostly so no one can accuse me of stealing an idea from it. If you have a really good sense of my characters, you might be able to predict which way a story will go. I’ve done it myself a couple of times with franchises I enjoyed. I don’t want you suing me for stealing your idea when we just happened to be thinking along the same lines, so I’m just not going to read your fic. Plus I really didn’t enjoy running a fever from that last fic I read, so I’m going to stay out of fanfiction for the sake of my health.

I wish you good writing, good learning, and someday a fictional universe of your very own to play with. Until then, be safe out there. The sanity you save may be your own.

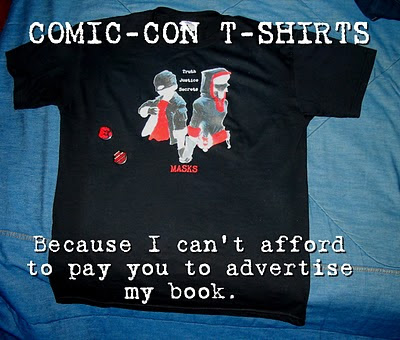

Okay, here’s how I put together the T-shirts the stylin’ Masks Posse wore to Comic-Con. These directions tell you how to create the image on a black T-shirt, which is considerably harder than on a white one. All images referenced in this post are available in this Photobucket album.

Okay, here’s how I put together the T-shirts the stylin’ Masks Posse wore to Comic-Con. These directions tell you how to create the image on a black T-shirt, which is considerably harder than on a white one. All images referenced in this post are available in this Photobucket album.