Someone recently referred me to thisWall Street Journal article about the increasingly horrifying levels of sex, violence, and generally objectionable behavior in young-adult fiction. They also included this set of YA author Libba Bray’s tweets on the subject of the same article, where she proclaims that this sort of reporting encourages those who ban books and try to keep controversial material out of the hands of young people who need the ideas it contains.

I agree with Ms. Bray, except when I don’t.

First, a statement of general policy. I don’t like book banning. I don’t like the idea that some people get to tell other people what they can and can’t read, unless the people doing the telling are copyright holders (who, in my view, have a complete right to control who does and does not see the material they produce, at least initially).

But I qualify that view in a very select set of circumstances—and parents selecting books for their children fall into one of those categories.

Don’t get me wrong—I think parents who try to keep everything remotely controversial away from their kids are missing the point of parenting. My mom used to tell me she wasn’t raising chickens for Colonel Sanders; she was raising eagles to fly. Before an eagle can fly, it needs a basic understanding of the world it flies in—at least when it comes to things like gravity. If you’re preparing your kids to be adults, you need to expose them to adult ideas at some point.

But that’s at some point. And one kid’s some point is not another’s.

Some kids can handle the bad stuff earlier than others, and it’s part of a parent’s job to figure out when a kid is ready for something. They won’t always do that job perfectly, which is why I encourage kids to seek out books that interest them and worry about reading levels and the like later. But where parents can provide guidance and context, they should. And if that means deciding a 13-year-old isn’t quite ready for Speak, then maybe it’s okay to wait until age 14 or 15. I’m not saying teens should never read a book like Speak; I’m saying some of them should wait longer than others to do so. And parents are better-equipped than many other people to determine their children’s maturity level.

My parents had a pretty liberal policy when it came to what we kids could read. Basically, as long as we stayed out of trouble and didn’t have violent nightmares about what we read, we were free to read whatever we liked. And so, despite growing up in the 1990s, when young-adult fiction was barely a twinkle in the publishing world’s eye and books for kids were a lot less graphic, I learned about a lot of scary grown-up concepts well before my peers did. By age 10, I knew a fair bit about rape, just from reading books for grown-ups and an article in, of all things, Reader’s Digest. By age 12, I had read enough Andrew Vachss to know a few things about child prostitution in Asian tourism, which alarmed my teachers like you wouldn’t believe. I read widely from my local library, with the result that my typical reading list might combine a book on human sacrifice with a manual on how to carve carousel horses. And though I had terrifying nightmares as a child, they were almost never the result of anything I read. Not even the carousel-horse books.

Now, I wouldn’t hand those books to an average twelve-year-old—certainly not my average classmate in the sixth grade. I could well imagine some of my peers having vivid nightmares about some of the things I read—or worse, going out and trying them out of sheer curiosity. But that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t have been allowed to read them. It just means that I was on the high end of the maturity curve for my age, and read accordingly. Similarly, I think kids who can handle the kind of darkness common in a lot of YA fiction should be allowed to read it if they want. Prior restraint—a fancy legal term for banning something before it’s happened—is not justified when it comes to kids in general reading books in general.

There is, however, one element of the WSJ article with which I agree. It’s not a cause for book banning, but I’d like to submit it as something for particularly daring YA authors to tackle. These relentlessly grim books lack something that I think is a crucial part of the teenage literary diet: hope.

I’m not saying every YA book needs to have a happy ending. But some of the dark ones should include, somewhere in them, a lessening of suffering. When you’re fifteen or sixteen years old, there are a lot of things in your life you can’t control. You usually can’t do anything about your parents acting insane, or the kids at school treating you like garbage, or the thousand-and-one things that seem to be wrong with your body. You need hope, whether you know it or not.

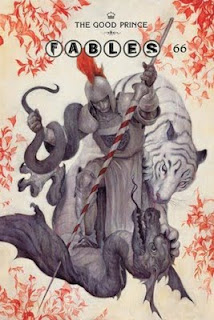

I remember my teenage years as a dark, crushing weight of hopelessness pressing down on my back, lightened only when I could escape into a story. I was never going to have any friends; I was never going to be loved or accepted; I was never going to be good enough for anyone to value me at all. I had been bullied consistently since I was eight years old, and the world around me seemed designed to support my tormentors. So while I didn’t go looking for hope (I didn’t think there was any to be had), I needed it. I secretly treasured stories where the good guys won, or at least didn’t completely lose, because it helped me think about my life in a way that made me want to change it. I read about characters who spat in fate’s eye, and learned to do that myself. So what if I wasn’t pretty enough, or popular enough, or from a rich family? I was smart, and I was stubborn, and I could be brave, and that might take me somewhere better than the place where I stood. So I kept writing, and made friends, and stood up to people who tried to break me. Stories, in the words of G.K. Chesterton, taught me that dragons could be killed.

Adults know that you can’t beat every monster, slay every dragon, right every wrong. But if we think we can’t fix any of that, we don’t try. And more monsters rise, and claim more victims.

So while none of my heroes have an easy road, there’s always at least a glimmer of hope that things might get better, that somebody can make a difference somehow. It would be nice if the doom-and-gloom patrol in YA fiction would take on that challenge.

Perhaps we’d all do well to remember the words of Robert A. Heinlein: “The last thing to come out of Pandora’s box was Hope.”

No comments:

Post a Comment