Pretty much for the hell of it, I’m going to start a companion series to Comic Books You Should Be Reading. I’m going to list the various unlikely subjects good writers—at least, good writers of contemporary non-literary fiction (read: fiction where stuff happens)—should be able to fake their way through. Let’s face it—unless we luck into a Kathy Reichs-like situation where we can write bestselling novels about our very favorite subject, in which we happen to be one of the world’s leading experts, most of us will have to do some research from time to time in order to write authoritatively about lives not our own.

But the problem with research for writers is that we tend to assume we know enough about most things to fake our way through it. And let’s face it, we tend to know a lot—as avid readers, we are usually autodidacts, filling our brains with useful information long before we pick up a pen. If you’re not at least a little bit of a trivia buff, you probably shouldn’t be a writer. But that doesn’t help you when you say something stupid in print and suddenly get a hundred emails from people who experience the situation you describe all the time and can tell you just how wrong you got it.

So here’s the first subject writers should know at least a little bit about: emergency medicine.

Let’s be honest—unless you’re going to write stories where nobody gets hurt, ever, or all injuries and accidents correspond exactly to events that have befallen you or your nearest and dearest, at some point a character will run up against a medical complication that requires expert help. And because nobody plans this kind of thing happening, it’s more dramatic and more realistic to have that misadventure be an emergency. And nothing you've seen on TV can be trusted. Writing an adventure story? You need to know what to do if one of your characters gets shot, stabbed, concussed, etc.—even if your characters are going to handle the situation wrongly. You need a good sense of how physical damage will affect your story, and for that you need research.

I count myself lucky in this regard—two of my best friends are former EMTs, a third is a medical assistant, and a fourth is a veterinary technician. There’s nothing like being able to call somebody up at a random time and say, “So my character was just shot in the head. What are my options if I want him to survive?” (Of course, I don’t actually have to ask this one, because one EMT has already made me lose my lunch with a graphic story about taking a call on a failed suicide who shot himself in the temple, severed both optic nerves, and lived—blind, but functional.) There is no substitute for cultivating friendships with people in the trenches. Reward them handsomely for their help, thank them lavishly in your acknowledgments, and listen to everything they have to say when they’re answering your question. You never know when a detail will turn out to be crucial.

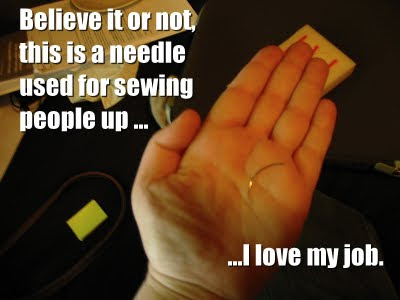

For example, I recently wrote a scene in which one of my characters gets cut and needs stitches, but can’t go to a hospital. Instead, he must talk another character through the process of stitching him up (the injury is to his back and he can’t reach it without help). The helper character, like me, has experience with sewing—but never with sewing anything that bleeds. My vet-tech friend came to my rescue, as the only person in my immediate circle who is allowed to stitch up patients. (According to one EMT, only qualified doctors can suture human beings—but the vet tech assures me that there isn’t a lot of practical difference between stitching up a human and stitching up, say, a pig.) She brought over a block of foam with some sample cuts, as well as two different kinds of curved needle and the type of thread used for sutures. She gave me a brief demonstration and then, content with her experience of my ordinary sewing abilities, sat back to watch me try.

The first thing I learned: I might be an artist with a straight needle, but I’m a klutz with a curved one. It doesn’t help much to push on the eye of the needle, and I could never really predict where the point would go once I pushed it into the “flesh.” I was quickly glad that my character would have a local anesthetic working when he got these stitches, and I had a new respect for Victor Frankenstein—those stitches were amazingly neat, while mine looked like a parade of drunken ants.

The second thing I learned: there’s no good place to grip a curved needle. It’s all going into the flesh at some point, of course, but the real problem is that once the point is in, so much of the curve is at a bad angle for my thick fingers that I had even less control over the needle’s direction than I expected, and I dropped the thing entirely several times. I quickly decided that my character would have to use the type of suture kit that comes with the suture permanently attached to a disposable needle, because otherwise the wound would never get stitched before the anesthetic wore off.

After several minutes of determined effort, I was ready to give up, and my foam “patient” was probably glad of it:

A few tips for aspiring writers who are looking to build their own emergency-medicine knowledge but can’t do EMT training:

A few tips for aspiring writers who are looking to build their own emergency-medicine knowledge but can’t do EMT training:

1. Make friends at your local fire station. When I was a journalism student, I was assigned the first-responders beat, and got to ride around in the fire truck and do all kinds of fun stuff. It wasn’t at all difficult to befriend the local firefighters once I explained who I was and why I was bothering them, especially since most fire stations are full of guys who basically do chores and paperwork all day while they’re waiting for that bell to ring. Asking respectful questions and carefully writing everything down (ask everyone to spell their name—it convinces them that you’re going to cite your sources) will take you pretty far, and be clear at the outset that if a call comes in, you will immediately get out of the way. Finally, simple comfort food is your friend here. Firefighters often have 24-hour shifts (minimum!), and a lot of their meals are either takeout or whatever the guy on mess duty can cook. My best interviews came after I showed up with a plate of homemade chocolate-chip cookies. Best of all, firefighters are much easier to befriend than police officers, who tend to be more wary of the press, and if you do need to talk to some cops, you can do worse than come in with a glowing reference from a fire captain.

2. Read reference books. Even if they’re boring, even if you don’t understand it all, something will sink in, and it will help you when you’re talking to the experts. Nothing makes a highly knowledgeable person like you better than a question like, “Okay, I understand that tetanus sets in when a wound is exposed to certain kinds of contaminants and stuff, but exactly where do you find those contaminants? Where’s the most unlikely source of tetanus you’ve found?” The preface says that you’ve done some homework and your source is not wasting his or her time; the follow-up question reassures your source that his or her expertise is indeed needed.

3. Seek out experts online. Dr. D.P. Lyle, M.D., has written some great books on how forensics work for mystery writers, and he has a very helpful website where he takes questions. Universities are another great source of experts; some, like California State University, Fullerton, have searchable “experts guides” that let you find faculty members who specialize in your area of inquiry. They’re a great resource as long as you are flexible about when they get back to you on your questions. I once interviewed a leading expert on urban planning and didn’t realize what a big deal he was until years later, when I noticed him being cited in a lot of other reference material I read.

Finally, and this is the most important lesson I’ve learned about research for writers—never be afraid to ask a (polite) question. In general, being clueless will take you pretty far, as long as you’re nice about it. And the questions you don’t ask will be the holes in your story …

No comments:

Post a Comment